Let's Debate NCLB And Testing - The Actual Policy

Plus a post recommendation for you to read

ICYMI - Some colleagues and I, in partnership with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, put out a paper on the business role in education reform. Business can provide some useful guardrails against the more extreme positions on both sides of the education debate. We need them back in the game.

Tom Kane, Dan Goldhaber, and I talked pandemic recovery on LinkedIn. Was all that federal money wasted? No. Was it as high leverage as it might have been? Also no.

Also if you missed the last WonkyFolk, it’s here.

Today I want to do a short post that basically suggests you to check out a longer one by Freddie deBoer. Regular readers know I consider him one of the sharpest reform critics out there. Maybe help him out and subscribe to his blog? I did not agree with everything in his Cult of Smart, but it’s must-reading if you operate in this sector in any kind of consequential role in the sense that, to paraphrase Mill, if you only know half an argument you don’t know it at all. His Substack is the same way and you might find yourself agreeing and disagreeing in equal measure.

DeBoer gets into the fraught topic of genetics and intelligence. It’s one of those issues where the received wisdom (on all “sides”) and what people actually working on the question talk about is very different. I agree with deBoer that an inclusive, meaningful, and kind economy and society has to provide opportunities for people who don’t have a specific kind of intelligence or go to a subset of colleges and universities. And I agree that material security is a predicate to freedom.

I disagree, though, about what we can and should expect from our education system in these regards. That’s why I come to work each day. And today’s post is an illustration of why. DeBoer writes,

As I put it exactly three years ago, you can define the problem with blank slate thinking in four words: No Child Left Behind. The most radical and destructive piece of educational policy in our country’s history, passed with remarkably broad bipartisan report, could only have been conceived of by those who believed that students have no intrinsic tendency towards a given performance level. And the result was disastrous - there was an immense waste of resources associated with NCLB, students and teachers and schools were suddenly forced to undertake inefficient and unnecessary census testing, and teacher tenure and unions were attacked. All because of a cheery and casually destructive insistence that every child was in possession of the same educational potential.

This is a strawman. It’s similar to the mischaracterization of NCLB in Ibram X. Kendi’s popular Stamped and a common one. There are plenty of reasons to be critical of NCLB, I welcome that debate, like most debates, because that’s how progress happens. But let’s try to be on point.

Advertisement:

Bellwether is hiring! Check out the opportunities here.

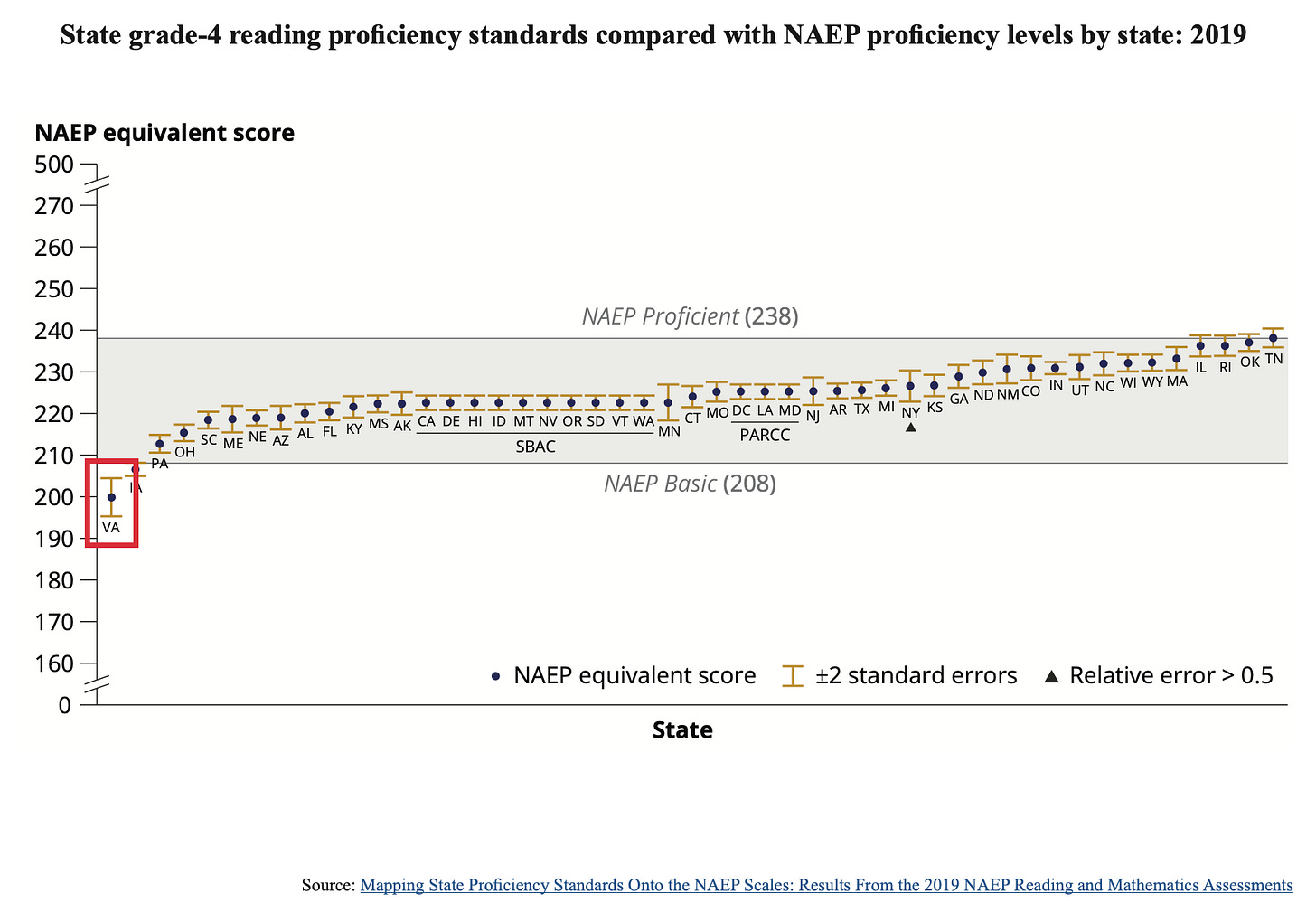

In this case, it’s important to remember that NCLB said states had to get kids to proficient on their own state tests. Both those features matter - their own tests, their own definitions of proficiency. It’s not widely understood just how minimal many of those proficiency levels are because of all the mischief in how states set cut scores (what it means to be at various performance levels) on those tests and the lack of transparency there. Forget alignment with NAEP proficiency, where there is serious disagreement about the quality of that specific performance level, there is a gap in many states between NAEP “basic” and “below basic” and what states report as passing and proficient. Figures as politically diverse as Arne Duncan and Glenn Youngkin have called this an “honesty gap.”

The argument for NCLB’s approach was not that all students would perform at a high level but rather that all (with some obvious exceptions) would at a minimal level. And that level will vary by state so you have to be specific there, too. This looks different in say Tennessee and Virginia. You can certainly disagree with that theory of action, but that’s the actual policy to debate and that we should debate. Should we expect schools to get almost all kids to a minimal level of proficiency or not?

(Also deBoer is correct that you don't have to do census testing for accountability at a school level but the problem is parents want to know where their own kids are at a point in time. Many teachers do, too. So do school district C-suites. It’s one of those things most everyone is for until they realize what it means in practice and are then like, what what?” And it’s why there are so many misaligned tests out there today in many places.)

In any event, his post today is worth checking out on the broader issues here.